The roar of the sea is a quiet constant at Okarito campground. Closer is the scrabbling sound of dinner – trying to escape.

On tonight’s menu is whitebait fritters. They couldn’t be fresher. Caught this morning, they are alarmingly alive, wriggling up the sides of the container in which they were delivered from the tent next door.

That’s where Paul lives during the whitebait season – heading out early every morning with net, boots and overalls. He’s one of several regulars who come for a season that runs from September through to mid-November. They live in tents, campers, old caravans or permanent cribs perched on the edge of remote inlets waiting for ‘the run’.

Whitebait can be caught up and down New Zealand coasts but South Westland is whitebaiter heartland. You can’t travel this bit of coast and not eat the delicacy that, right now, is all eyes and whipping tail. Several have made it to the top of the yoghurt container – I give it a shake, pop a paper towel over the top and start planning an early dinner.

These vigorous wrigglers are the young of native trout- mainly Inanga but also Koaro and banded Kokupu – which spend part of their life-cycle in the sea and part in fresh water.

Mature fish lay their eggs in grasses that are covered in water during high Spring tides and there they stay until the next high tides wash them out to sea where they grow over the winter before migrating back up through estuaries and streams in late Winter and Spring.

That’s where the nets are waiting. The road down to Jackson Bay crosses several rivers where permanent piers jut into out into the slow-flowing waters and whitebaiters cluster in the evening light. It might look like a formidable set of hurdles for the young trout but whitebaiting rules do allow free home runs outside set hours for fishing or in certain protected estuaries.

This year’s catch has been good on parts of the coast. At Waita River mouth (just North of Haast) some of the regulars were heading home early because rewardingly vigorous runs had already filled freezers with excess helping pay for the fishing trip.

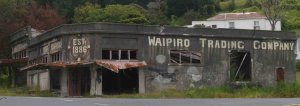

Waita is where Tony and Moana operate Curly Tree Whitebait Company dispatching the delicacy to restaurants, retailers and enthusiastic foodies around the country. On what was once an old airstrip, they also run a fresh foodstall serving the best whitebait fritters you can buy anywhere on the coast.

These are pure whitebait, held together with a bit of egg – though Moana now favours her mother’s even more basic recipe – no egg at all. Just whitebait chucked straight onto the hotplate with a sprinkling of garlic salt. She’s right. That’s the best way to eat them.

But – back at the Okarito camp, I hadn’t yet met Moana – and along with his freshly caught whitebait, Paul had given us a free-range egg. So, as instructed, I mixed the egg with no more than a spoonful of flour, tipped in the still wriggling bait, ignored the staring eyes and lashing tails, and plopped them into a heated pan.

My first home-made whitebait fritters were bloody fantastic.